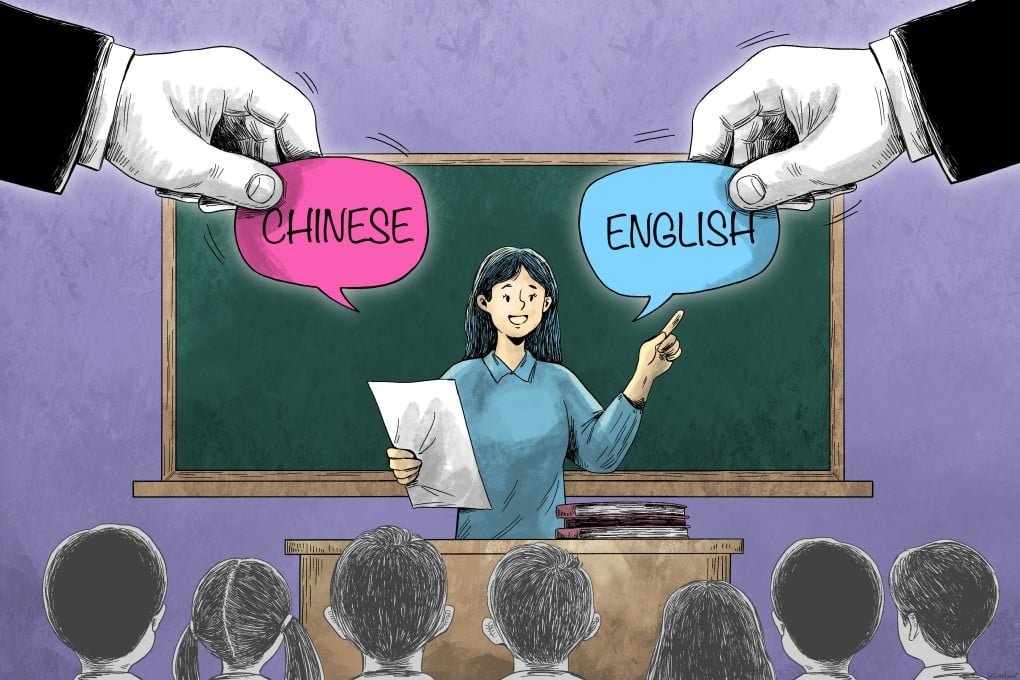

Students and educators weigh the benefits and pressures as authorities review policy on language of instruction in junior secondary education

When Suri Chan Tin-wing began her first compulsory literature course at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, she found herself hesitating over a three-hundred-word creative writing assignment.

Despite choosing to major in English, the nineteen-year-old felt unprepared to craft a confident short story, having studied in a secondary school where most subjects were taught in Chinese.

At Yan Chai Hospital Law Chan Chor Si College in Kowloon Bay, only science subjects such as mathematics and biology were delivered in English, while the school otherwise adopted Chinese as its medium of instruction.

Chan said the transition to an English-dominant university environment exposed gaps in her vocabulary and writing fluency.

“I felt hesitant the moment I started writing,” she said, recalling how she compared herself with peers from English-medium schools.

“I questioned whether my plot would be as well written or creative as those of students from EMI schools.

I thought my writing was formulaic and lagged behind.”

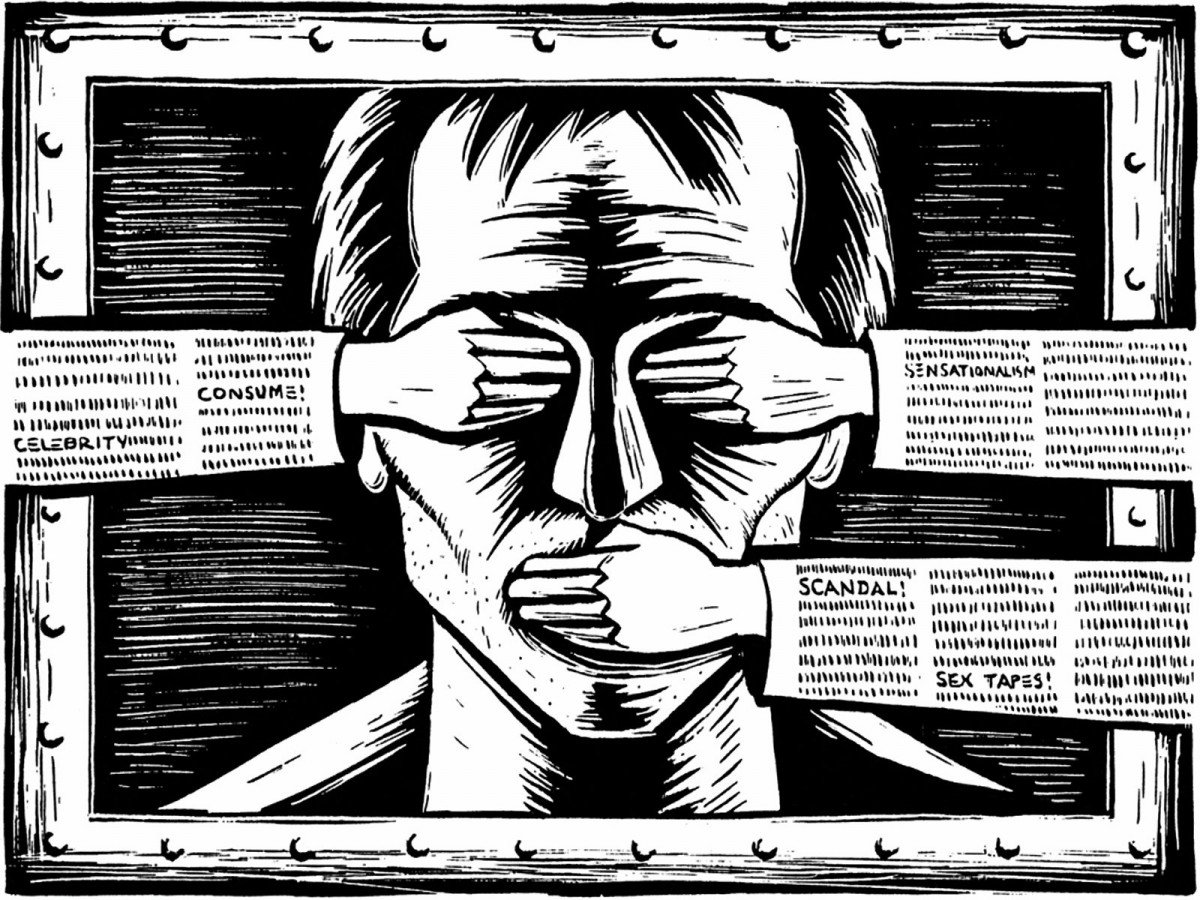

Her experience reflects a broader discussion now unfolding across Hong Kong’s education sector.

Authorities are reviewing the long-standing policy on medium of instruction, with expectations that more junior secondary schools may be permitted to teach in English.

Supporters of expanding English-medium instruction argue that stronger exposure to the language at an earlier stage can better equip students for tertiary education and international engagement.

English remains one of Hong Kong’s official languages and plays a central role in higher education, business and global communication.

However, educators caution that rapid expansion could present academic challenges for some pupils.

Research and classroom experience suggest that students who lack sufficient foundational language proficiency may struggle to grasp complex subject content when it is delivered in a second language.

They warn that academic confidence and conceptual understanding must not be compromised in pursuit of policy goals.

The issue also carries institutional implications.

A veteran involved in shaping medium-of-instruction policy over the years noted that the designation of a school as English- or Chinese-medium can affect enrolment patterns and public perception, influencing a school’s competitiveness and long-term viability.

For students like Chan, the debate is deeply personal.

While she has gradually gained confidence and strengthened her writing skills at university, she believes earlier immersion in English could have eased her transition.

As policymakers consider adjustments to the framework, balancing opportunity with preparedness remains central to ensuring that language reform enhances, rather than hinders, pupils’ development.

Despite choosing to major in English, the nineteen-year-old felt unprepared to craft a confident short story, having studied in a secondary school where most subjects were taught in Chinese.

At Yan Chai Hospital Law Chan Chor Si College in Kowloon Bay, only science subjects such as mathematics and biology were delivered in English, while the school otherwise adopted Chinese as its medium of instruction.

Chan said the transition to an English-dominant university environment exposed gaps in her vocabulary and writing fluency.

“I felt hesitant the moment I started writing,” she said, recalling how she compared herself with peers from English-medium schools.

“I questioned whether my plot would be as well written or creative as those of students from EMI schools.

I thought my writing was formulaic and lagged behind.”

Her experience reflects a broader discussion now unfolding across Hong Kong’s education sector.

Authorities are reviewing the long-standing policy on medium of instruction, with expectations that more junior secondary schools may be permitted to teach in English.

Supporters of expanding English-medium instruction argue that stronger exposure to the language at an earlier stage can better equip students for tertiary education and international engagement.

English remains one of Hong Kong’s official languages and plays a central role in higher education, business and global communication.

However, educators caution that rapid expansion could present academic challenges for some pupils.

Research and classroom experience suggest that students who lack sufficient foundational language proficiency may struggle to grasp complex subject content when it is delivered in a second language.

They warn that academic confidence and conceptual understanding must not be compromised in pursuit of policy goals.

The issue also carries institutional implications.

A veteran involved in shaping medium-of-instruction policy over the years noted that the designation of a school as English- or Chinese-medium can affect enrolment patterns and public perception, influencing a school’s competitiveness and long-term viability.

For students like Chan, the debate is deeply personal.

While she has gradually gained confidence and strengthened her writing skills at university, she believes earlier immersion in English could have eased her transition.

As policymakers consider adjustments to the framework, balancing opportunity with preparedness remains central to ensuring that language reform enhances, rather than hinders, pupils’ development.