David Siegel warns that China must shift from high-volume price rivalry to breakthrough technology if it is to escape 'involution' in sectors like EVs and food delivery

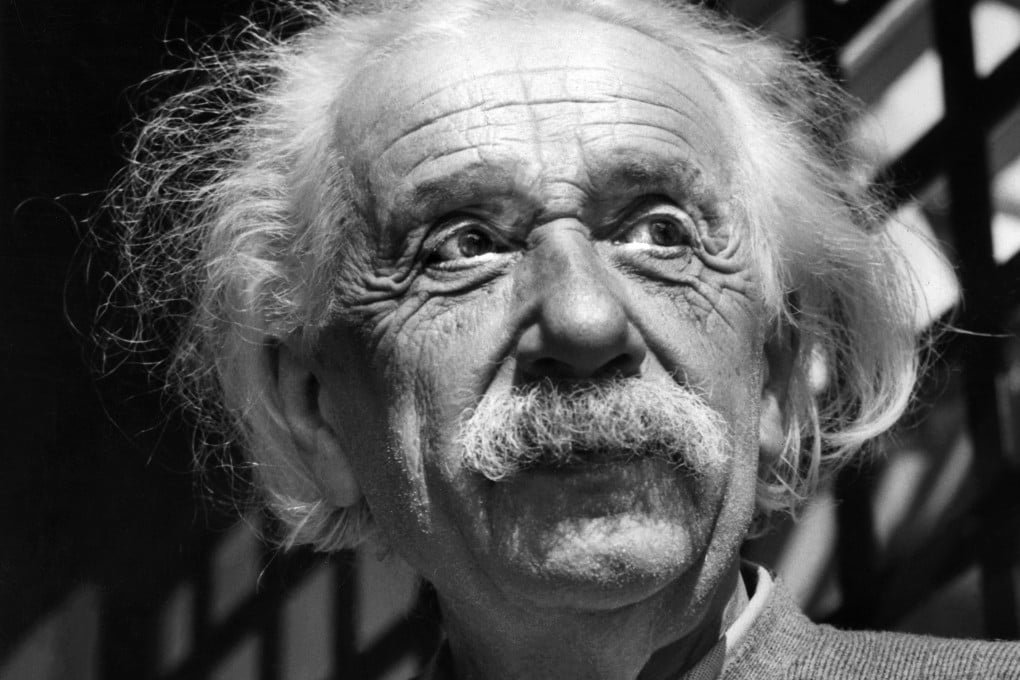

David Siegel, co-founder and co-chairman of the hedge fund Two Sigma, told the Family Business Summit in Hong Kong that the answer to China’s so-called “involution” is not more of the same fierce price competition but deeper innovation.

He said that in markets where companies are locked into low-margin battles — for example in electric vehicles and food-delivery platforms — what emerges is a hyper-competitive loop that benefits no one.

“In the areas where you’re getting excessive competition, it’s because the business is already commoditised,” Mr Siegel said.

“If you move into the domain of far more innovative technology, something much more specialised, something that is not already ready for scale deployment, it’s a different story.” His remarks reflect Beijing’s growing concern about the term _neijuan_ — the societal and economic spiral of intensified competition with minimal gains —which President Xi Jinping referenced last year when warning against “involution-style vicious competition”.

Mr Siegel pointed out that many Chinese firms have duplicated one another in fast-growth sectors, driving prices and margins down as rivals battled for market share rather than differentiation.

By contrast, those developing next-generation technologies or new business models are less exposed to price-driven collapse and may offer higher value for society and the economy.

He emphasised that China’s private-sector resources and scale are well-placed to lead in specialised innovation if the policy setting supports it.

That means directing capital, talent and regulatory attention away from cut-price volume sectors and toward fields that demand advanced engineering, strong intellectual property and high entry-barriers.

Mr Siegel’s comments come amid broader debate in China around how to move from volume-led growth toward higher-quality development.

With demographic headwinds and slower consumption, the competitive advantage of racing to scale at low cost is diminishing.

His message was clear: the way out of the involution spiral is not price cutting but generating breakthrough capabilities.

For Chinese companies, this means choosing fewer battles in commoditised fields and aiming for the frontier of technology instead.

As China navigates its next stage of economic transformation, Mr Siegel believes that firms and policymakers alike must recognise that true competitive advantage lies in innovation, not in being the fastest or cheapest.

The implications are significant: the country’s allocation of talent, regulation and investment must shift accordingly.

He said that in markets where companies are locked into low-margin battles — for example in electric vehicles and food-delivery platforms — what emerges is a hyper-competitive loop that benefits no one.

“In the areas where you’re getting excessive competition, it’s because the business is already commoditised,” Mr Siegel said.

“If you move into the domain of far more innovative technology, something much more specialised, something that is not already ready for scale deployment, it’s a different story.” His remarks reflect Beijing’s growing concern about the term _neijuan_ — the societal and economic spiral of intensified competition with minimal gains —which President Xi Jinping referenced last year when warning against “involution-style vicious competition”.

Mr Siegel pointed out that many Chinese firms have duplicated one another in fast-growth sectors, driving prices and margins down as rivals battled for market share rather than differentiation.

By contrast, those developing next-generation technologies or new business models are less exposed to price-driven collapse and may offer higher value for society and the economy.

He emphasised that China’s private-sector resources and scale are well-placed to lead in specialised innovation if the policy setting supports it.

That means directing capital, talent and regulatory attention away from cut-price volume sectors and toward fields that demand advanced engineering, strong intellectual property and high entry-barriers.

Mr Siegel’s comments come amid broader debate in China around how to move from volume-led growth toward higher-quality development.

With demographic headwinds and slower consumption, the competitive advantage of racing to scale at low cost is diminishing.

His message was clear: the way out of the involution spiral is not price cutting but generating breakthrough capabilities.

For Chinese companies, this means choosing fewer battles in commoditised fields and aiming for the frontier of technology instead.

As China navigates its next stage of economic transformation, Mr Siegel believes that firms and policymakers alike must recognise that true competitive advantage lies in innovation, not in being the fastest or cheapest.

The implications are significant: the country’s allocation of talent, regulation and investment must shift accordingly.