Judge upholds designation under Section 1260H despite majority of DoD claims being rejected

A U.S. District Court has ruled that Shenzhen-based DJI must remain on the Pentagon’s list of Chinese companies allegedly linked to Beijing’s military, rejecting the firm’s challenge to its classification under Section 1260H of U.S. law.

The decision constrains DJI’s access to federal programs and underscores Washington’s expansive view of national-security authority.

In its appeal filed this week, DJI sought reversal of a September lower-court finding that its inclusion on the blacklist was legally justified.

The firm had argued it is neither owned nor controlled by the Chinese military, and that its product line focuses on civilian and commercial drones rather than defense systems.

In the earlier lawsuit, DJI described the designation as “unlawful and misguided,” citing damage to its reputation and business relationships.

Judge Paul Friedman’s ruling acknowledged that DJI’s corporate structure does not neatly align with the Department of Defense’s most severe allegations—such as direct Communist Party control—but upheld the designation on a narrower ground.

He found that the government had demonstrated DJI contributes to China’s defense industrial base through “military-civil fusion” mechanisms, including its recognition by the Chinese government as a National Enterprise Technology Center and the receipt of subsidies and preferential tax treatment.

Notably, the judge dismissed several claims from Pentagon arguments as insufficiently evidenced, finding that the Department had conflated industrial zones and overreached in justifying ownership ties.

But the court held that the dual-use nature of DJI’s drone technologies, combined with its government support, falls within the broad discretion afforded to the DoD under Section 1260H.

The ruling does not impose a consumer ban on DJI products in the United States, but it sustains major restrictions on government contracts, grants, loans and program eligibility.

DJI says it is disappointed by the outcome, describing the decision as resting on a singular rationale applied unevenly among private firms, and is reviewing its appellate options.

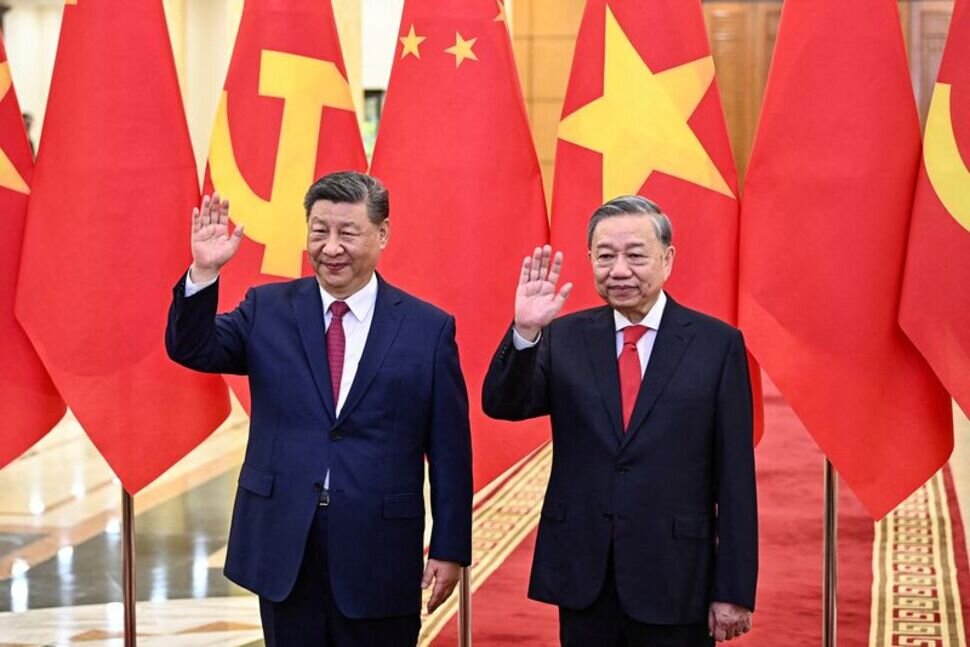

The case follows a broader U.S. approach toward Chinese tech firms regarding national security risks.

It arrives amid looming import and procurement bans facing DJI under laws such as the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act and provisions of the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, which require the company to demonstrate its products pose no unacceptable national security risks by late this year.

With the designation intact, DJI’s operations in its largest foreign market face heightened constraints while the company assesses paths to restore access and defend its standing in U.S. legal and trade systems.

The decision constrains DJI’s access to federal programs and underscores Washington’s expansive view of national-security authority.

In its appeal filed this week, DJI sought reversal of a September lower-court finding that its inclusion on the blacklist was legally justified.

The firm had argued it is neither owned nor controlled by the Chinese military, and that its product line focuses on civilian and commercial drones rather than defense systems.

In the earlier lawsuit, DJI described the designation as “unlawful and misguided,” citing damage to its reputation and business relationships.

Judge Paul Friedman’s ruling acknowledged that DJI’s corporate structure does not neatly align with the Department of Defense’s most severe allegations—such as direct Communist Party control—but upheld the designation on a narrower ground.

He found that the government had demonstrated DJI contributes to China’s defense industrial base through “military-civil fusion” mechanisms, including its recognition by the Chinese government as a National Enterprise Technology Center and the receipt of subsidies and preferential tax treatment.

Notably, the judge dismissed several claims from Pentagon arguments as insufficiently evidenced, finding that the Department had conflated industrial zones and overreached in justifying ownership ties.

But the court held that the dual-use nature of DJI’s drone technologies, combined with its government support, falls within the broad discretion afforded to the DoD under Section 1260H.

The ruling does not impose a consumer ban on DJI products in the United States, but it sustains major restrictions on government contracts, grants, loans and program eligibility.

DJI says it is disappointed by the outcome, describing the decision as resting on a singular rationale applied unevenly among private firms, and is reviewing its appellate options.

The case follows a broader U.S. approach toward Chinese tech firms regarding national security risks.

It arrives amid looming import and procurement bans facing DJI under laws such as the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act and provisions of the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, which require the company to demonstrate its products pose no unacceptable national security risks by late this year.

With the designation intact, DJI’s operations in its largest foreign market face heightened constraints while the company assesses paths to restore access and defend its standing in U.S. legal and trade systems.